|

We began the week by identifying the four traits of a strategic leader:

We continued by describing four barriers to strategic leadership”

As part of yesterday’s work, I asked you to make a list of all the things you’d done over the previous day (or days). Today, we flip that around. Take a few minutes now and make a list of all of the things you did not get done!

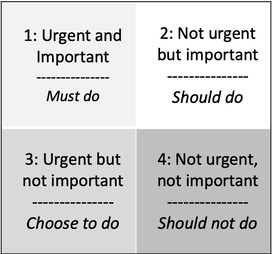

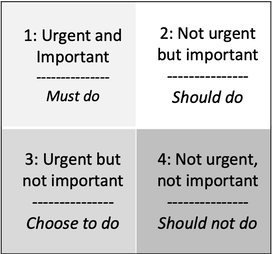

Now plug them into the matrix. Notice anything? If you are like some of us, many of your uncompleted tasks will fall in quadrant 2. This is just one more reminder that we can be more driven by urgency than by importance. Now, compare what you did in quadrant 3 with what you didn’t do in quadrant 2. You can think of this as a strategic deficit. While quadrant 1 activities are largely unavoidable, quadrant 3 activities are avoidable. All the time that you spent in quadrant 3 was time you could have invested in quadrant 2. That quadrant 3 time is your strategic deficit! Next week we’ll start digging into why we would spend time in quadrant 3 instead of investing time in quadrant 2. If you want to get a head start on that work, spend a few minutes reflecting today or this weekend. When you chose to act on specific quadrant 3 issues, why did you make those choices? What criteria did you use in choosing between urgent and important? If you’ve enjoyed this week’s focus, send me an email by clicking here and telling me what had the biggest impact on you this week. Do good and be well, Frederick

0 Comments

We began this series by looking at the four traits of a strategic leader:

To better assess our own level of strategic leadership, we’ll use the Eisenhower Matrix to evaluate how we spend (or invest) our time. The Eisenhower Matrix is named for the former President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower. In a 1954 speech, Eisenhower quoted “a former college president” as saying "I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important.”[1] It has been popularized by Stephen Covey in his book, the Seven habits of Highly Effective People (Covey, 1989). The Eisen however Matrix consists of four quadrants formed by the intersections of urgent/not urgent and important/not important: The treadmill of the urgent refers to our propensity for focusing on quadrants one and three and neglecting quadrant two. This is problematic as, by definition, strategic work is rarely urgent as it is future focused. Most strategic work takes place in quadrant two.

The Eisenhower Matrix has two primary uses:

Knowing how we spend our time and understanding that we could do better lay the foundation for a future in which we adopt the mindset of a strategic leader, which is where we are headed next week. You can leverage the power of the Eisenhower Matrix in two steps. First, take five to ten minutes and create a list of all of the different things you have done in the past day (or five days if you have the time). After you are done, determine which quadrant each of the tasks falls into. Second, look closely at quadrants 1 and 3. Many of us have a difficult time separating the urgent and important from those that are urgent but not important. Urgency has a powerful effect on us and we tend to assume that something is important because it is urgent. How can we distinguish between quadrants 1 and 3? There will always be a subjective component to it, but here are some things that might indicate something you placed in quadrant 1 should actually be in quadrant 3:

What do you see? Quadrant 2 is where the most important strategic decisions and actions occur. Many tasks in Quadrant 1 are unavoidable, but do you have to be the one to do them? Finally, look at quadrant 3. By definition, investing time in quadrant 2 is more important than investing in quadrant 3. How much time did you spend in quadrant 3, and what might you have been able to do if you had invested that time in quadrant 2? You may notice that I refer to spending time in quadrants 1 and 3 but investing time in quadrant 2. That’s because time spent in quadrant two pays dividends. We’ll look at that more closely later. Please take a few minutes to reflect on how you spend your time, especially in regard to quadrants 1 and 3. Do good and be well, Frederick Happy Tax Day! Oh, wait, that’s not a thing this year (until later). Silver lining?

Yesterday we discussed two of the barriers to strategic leadership: being overwhelmed by the urgent and lacking clarity of purpose. Today, we’ll explore the other two:

We are infatuated with big change because we want to be inspired and we believe in magic bullets. Big change rarely works. In the future we will go into depth as to why it doesn’t, but for today let’s focus on inspiration and magic. A grand vision for change is exciting. These visions are usually led by highly placed champions who can bring significant resources to the effort. The effort, especially in the early stages when support is concentrated and plentiful, can energize people across the organization, create a sense of shared purpose, and spur collaboration across silos. These are all great things but unfortunately, they often don’t lead to the changes we had hoped for. Again, we will look at why in the near future. The idea of a magic bullet is compelling. If we could just do this one thing, or just change this one thing, then our world would be better. There are obviously significant issues that, if “fixed” could substantively improve the organization. Unfortunately, the complex nature of organization, and the people living within them, means that most issues will require many smaller solutions as opposed to one big one. Organizations simply aren’t structured to respond to single-focus changes. Additionally, when we rely on magic bullets, we wind up ignoring what Jim Collins referred to as “the brutal facts of reality” (Collins, 2001, p. 69). In this world, magic is rarely able to alter reality, unless you are JK Rowling or a similarly gifted storyteller. Many of us lack the training and skills to be leaders. Ouch! That’s not an indictment on leaders, it is merely an observation based on how we choose our leaders. Most people rise to leadership positions based on several behavioral traits:

Ironically, some of our biggest leadership challenges correspond to the strengths that got us into leadership roles in the first place.

In addition to these issues, the way leaders are trained can also undermine our ability to grow in our jobs. Some of us are promoted with no leadership training while others may participate in leadership degree programs or intensive workshops. Formal programs usually offer a strong background in understanding the theories that drive leadership and organizations. The big problem is that formal training usually occurs before we take a position, is unable to account for each of our unique contexts and lacks on-site follow up. Once we move into our roles, the amount of training drops precipitously and what training there is usually occurs off-site, is decontextualized, and lacks follow through. To add insult to injury, many organizations underinvest in leadership development and support. leadership coaching is often a luxury reserved for only the highest hierarchical tiers of the organization. It’s easy to feel a bit pessimistic in the face of these four barriers (overwhelmed by the urgent, unclear purpose, big change, lack of training). Tomorrow we’ll look at a tool that can help you become more aware of some of these barriers. On Friday will do some serious reflection, and next week we’ll start working on developing the mindset of a strategic leader. Here are two questions to help you reflect on today’s concepts:

Do good and be well, Frederick Yesterday we talked about the four traits of a strategic leader: 1.Acting with intention on a daily basis 2.Solving problems 3.Enacting relentless incremental change 4.Developing people We discussed how these four traits interact with each other and amplify the daily actions that leaders take. We also enumerated four barriers and today we’ll look at the first two.

It is not only that the treadmill of the urgent consumes our time, but it actually degrades our ability to engage in strategic action. In fact, the first goal of becoming a strategic leader is to get off the treadmill of the urgent! First, when we focus on the urgent, we make it a higher priority that the important. Obviously, there are many issues that are both urgent and important but focusing on the urgent leads us to be reactive and over time we react to urgent matters even if they are not important! In fact, we may even consciously put off important matters in favor of urgent, but not important, issues.

Second, consistently working on urgent tasks uses a different set of skills than acting strategically, and our strategic skills atrophy over time. We become really good at reacting to crises, but we forget how to invest proactively. Our patience and ability to dissect and reconstruct complex issues degrade, creating a negative cycle in which we invest more time in what we are good at (responding to crises) and less in what we aren’t good at (investing proactively). Finally, urgent tasks usually are not strategic tasks. Urgent tasks are, by definition, focused on the present, while strategic tasks are focused on the future. Further, urgent tasks are generally more about symptoms as opposed to root problems and thus perpetuate a cycle of having to deal with the same issues multiple times. A focus on urgency creates an infinite loop of treating the same reoccurring symptoms with the result that we are in perpetual motion yet never moving forward. Ironically, many leaders actually thrive on urgency. Running from task to task all day long, a leader can feel as if they have achieved many things. The problem is that urgent is not the same as important. Our inclination to respond to the urgent often means that we ignore the important. So, at the end of the day we have checked off many items, but nothing has really changed. The second barrier is a lack of clear purpose. This can be puzzling as it seems like our purpose is obvious. Educational leaders’ purpose is to help students learn. Health care administrators help patient heal. Sales leaders help customers fulfill a specific need. However, the complexity of organizations leads to confusion about what the real purpose of the organization is. Most organizations have multiple and sometimes conflicting purposes. For example, in any organization, these different purposes could be at work:

These don’t even include the purposes that individuals bring to the organization. For example:

With multiple purposes, what’s important may not be clear because the question becomes “important to whom?” While these barriers are significant, there is a way forward. In coming weeks, we will walk that path, but tomorrow we’ll look at the other two barriers, infatuation with big change and a lack of training and skills. Before you go, think about the purpose of your organization as well as the purpose of your own leadership. Are they clear? Do they align? What about those you serve? Do they share your clarity (or confusion)? Do good and be well, Frederick There are four traits to being a strategic leader:

Acting with intention sounds like something we all do, but the fact is that most of us spend too much time responding and reacting. Strategic leaders view events through a lens of purposefulness. They choose where and when to engage and do so in ways that not only address the immediate, but that also move things closer to the vision. By being intentional, strategic leaders invest more of their time for long term benefit and spend less of it on putting out fires. Being intentional means we structure our work around important (as opposed to urgent) priorities. Solving problems may seem like we do all day long but this isn’t actually the case. Most of the times, we are actually treating symptoms instead of problems. Treating symptoms is a temporary fix and symptoms will reoccur, demanding additional amounts of our time. However, with increased intention, we can uncover and address root problems. Focusing on root problems prevents symptoms from reoccurring and allows us to reinvest saved time into efforts that further our purpose and values. Enacting relentless incremental change isn’t as glamorous as doing “big” change, but it is more effective over time. Strategic leaders look at situations and ask, “what is one thing I can do right now that will make this a little bit better?” Incremental change allows for constant improvement and builds momentum for more significant undertakings. It also results in more effective use of resources because efforts that don’t work required minimal resources. Developing people is at the heart of leadership. It is easy to forget that as we are consumed with day-to-day operations, but if every team member/employee was 30% better, wouldn’t the organization and our outcomes also be 30% better? Strategic leaders understand that the single most important thing they can do to improve organizational performance is to improve their people and they develop core strategies that help them focus on that. Each of these four things works together and are components of an integrated strategic leadership approach. Acting with intent helps us differentiate symptoms and problems. Engaging in incremental change allows us to improve problems immediately. Solving problems helps us improve lives for our team members and allows us to invest more time in helping them grow. If being a strategic leader is so clear cut, why is it so hard? There are four barriers to being a strategic leader:

Tomorrow, we’ll look at the first two barriers but before leaving, think about your own leadership. Of those four traits (acting with intention, solving problems, enacting incremental change, and developing people) which are your strengths? Which ones do you need to grow in? Do good and be well, Frederick |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed